17 April 2015

With the general election looming in Britain and the parties publishing their manifesto documents over the past five days, we should have a clearer idea what the next Parliament might deliver for football fans, no?

Football matters in Britain. Each week, 1.96m people play. Every season, nearly 25m people pass through the turnstiles of the clubs that make up the country’s top two tiers. Sky Sports has found its way into more than 7m homes, in which around 1.2m people on average watch each of the top-flight games they broadcast.

Supporter activism in England has never been more sophisticated or vocal. Assisted by organisations such as Supporters Direct (SD) and the Football Supporters’ Federation, and backed by over 100 Supporters Trusts, football’s resurgent popularity has risen in conjunction with a growing politicisation of its supporter base.

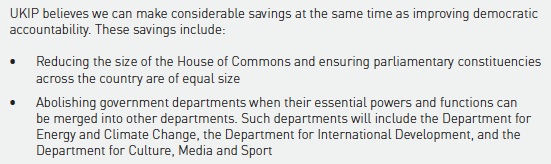

So you’d think that maybe the parties would engage, actively, with this demographic. Well I’ve looked at those manifestos and I’m not convinced. Do make up your own mind, of course: the Conservative Party manifesto is here. The Labour Party manifesto is here. And the Lib Dem manifesto is here. (For this particular exercise, we do not need to bother with the UKIP manifesto because there is no mention of football in it, and the only mention of sport is when they propose the abolition of the Department for Culture, Media and Sport, below right).

What about the Tories? Given that greater supporter democracy often involves a direct challenge to the free-market ethos that dominates our national game and the fact that the Conservatives have largely dispensed with their ‘touchy-feely’ window dressing, this time around the Tories have nothing to say on the issue.

The only mention of football in their manifesto refers to the introduction of more artificial pitches for community use, without specifying any amount of pitches, or any amount of money to be set aside for them.

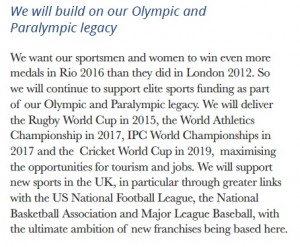

The Tory party does, curiously, set aside more space to say they will support ‘new sports in the UK, in particular through greater links with the US National Football League, the National Basketball Association and Major League Baseball, with the ultimate ambition of new franchises being based here.’

Eh?! Not a word about how to help football clubs or their fans, but active work towards getting NFL, NBA and MLB teams based in the UK? (See left).

Eh?! Not a word about how to help football clubs or their fans, but active work towards getting NFL, NBA and MLB teams based in the UK? (See left).

Unlike the disinterested Tories, the Liberals, who still represent theoretical potential partner for both the main parties in the advent of coalition, at least address football three times, saying they will criminalise homophobic chanting at games, foster an environment for safe standing, and they also touch on the issue of supporter democracy.

In their manifesto, the Lib Dems promise to “give football fans a greater say in how their clubs are run by encouraging the reform of football governance rules to promote engagement between clubs and supporters.” In short, exactly the kind of vapid, vaguely-worded ‘non-commitment’ that is guaranteed to really get the pulse racing.

So, as has so often been the case over the past 20 years, those who want a greater role for fans within the game look to Labour instead.

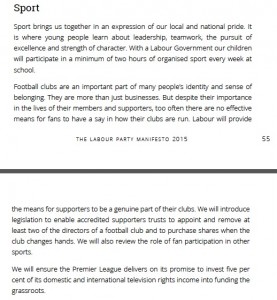

Although not proposing anything as radical as a Sports Law (explored in greater detail lower down), the party manifesto does contain some interesting proposals, specifically: “Labour will provide the means for supporters to be a genuine part of their clubs. We will introduce legislation to enable accredited supporters trusts to appoint and remove at least two of the directors of a football club and to purchase shares when the club changes hands.”

Back in October of 2014, when this commitment was first presented, Clive Efford MP, Labour’s Shadow Sports Minister, provided some finer detail about how legislation might work in action.

Under the Labour plan the Government would introduce a legally enforceable right for a Supporters Trust to appoint up to a quarter or a minimum of two of the directors and obtain (under an obligation of confidentiality) financial and commercial information about the business and affairs of a football club. Allied to this, fans could also purchase up to 10 per cent of the shares when a club changes ownership. The buyer acquiring control – defined as 30 per cent – would have to offer the Trust up to a tenth of the shares they were purchasing for 240 days following the deal.

Speaking at the launch, Efford said “Too often fans are treated like an after-thought as ticket prices are hiked-up, grounds relocated and clubs burdened with debt or the threat of bankruptcy. The Labour Party has listened to the views of fans about changing the way football is run in England and Wales. And we want to ensure they are heard by the owners of the clubs too.”

Whether these proposals will amount to anything will depend not just upon Labour winning power (far from guaranteed) but that any future Labour Government has the will and the time to push through such measures. Given their track record, nobody should hold their breath. And let’s be honest, the party’s entire section on sport in their manifesto amounts to 188 words (below right, click to enlarge). That almost certainly reflects how important it is to them in the grand scheme of things.

During the run-up to the last election the two main political parties made vague attempts to woo this element of the electorate. In the red corner, Labour pledged to “develop proposals to enable registered Supporters Trusts to buy stakes in their club”, while the Tories promised “to reform the governance arrangements in football to enable co-operative ownership models to be established by supporters”.

Did you notice that happen? Me neither.

The problem is such aspirations rarely come to fruition and despite what was promised, when the coalition Government whimpered into power, supporter democracy got dropped. In fact, the only concrete change in this sphere came into life as an indirect consequence of the 2011 Localism Act.

Under this, communities, and by extension local organisations such as Supporters Trusts, now have the right to bid for ‘assets of community value’. The idea behind this piece of legislation is to ensure that land and buildings of value to communities, such as village shops, pubs and even football stadiums, are not taken away from local people without them first having an opportunity to purchase the asset.

For an asset to become officially of ‘community value’, an application must be made to the local authority which will then judge whether it can be added to its list. If the application is successful then should the asset come up for sale, the community organisation that made the request is given a six-week period to decide if it wants to make a bid for it. If it does, then it has a further six months to raise the necessary finance, effectively delaying any sale.

Several Supporters organisations, including those at Manchester United, Liverpool and Birmingham City, have already had their club’s stadiums added to the local authority’s list of community assets, which theoretically should make Old Trafford, Anfield and St Andrews that bit harder to flog off.

But despite a welcome introduction, all the Act really provides supporter groups with is the right to bid for an asset. Trusts are not seen as preferential bidders and nor are they provided with first refusal on the sale. It also represents a fraction of what was promised. Fans were led to believe that meaningful reform was on the agenda and not, as transpired, just some tinkering around the edges.

It’s been a long-time since any government took the issue of supporter democracy seriously. The last great leap forward in this area came back in 2000 when Labour introduced SD, a new organisation with a remit to assist in the creation of Supporters Trusts and the extension of fan ownership within English football.

Since inception, SD has done some fantastic work. “Over the past 15 years, we have helped in the creation of 104 Supporters Trusts in English football, 73 of which are in the top four divisions” says Kevin Rye of SD. “And many of these Trusts have done great thing.

“We have some that have saved clubs, such as at York City, Portsmouth and Exeter City. Others that have created new clubs, such as AFC Wimbledon, Enfield Town FC and FC United of Manchester. And the movement even possesses a number of Trusts that have managed to get a foothold in the Premier League, at both Arsenal and Swansea.”

Even without ownership, both Supporters Trusts and other fan organisations have done much to hold their clubs to account over the course of the past 15 years, often acting as a focal point for campaigns against ‘the board’.

It was the Newcastle United Supporters Trust that led the recent campaign for the reinstatement of St James’ Park as their stadium’s name, the Spirit of Shankly (the Liverpool supporters union) that has lately confronted the club over ticket prices and the Cardiff City Supporters Trust that tirelessly campaigned for the club to revert back to its traditional blue colours.

A key element in the expansion of supporter democracy has been the politicisation of fans that has taken place in England. In the book I recently wrote on the history of supporter activism and ownership in this country (Punk Football) I was amazed at just how far fans have travelled psychologically over the past three decades. The right to protest appears natural today but that wasn’t always the case.

For much of the 20th century, football activism in England barely existed. From the professional game’s inception until the mid-1980s, fans primarily regarded themselves as customers, albeit customers with an almost pathological sense of brand loyalty. Where club-level organisation existed it was only in the form of supporters clubs.

The attitude of the overwhelming majority of those involved in these organisations was best exemplified in the motto of the National Federation of Football Supporters’ Clubs, which had been established in 1926. The aim of both the national organisation and its constituent members was to ‘Help and not to Hinder’. What this amounted to was a willingness for fans to give their time and money to their teams but to expect nothing back in return.

This began to change in the 1980s as supporters slowly became more political; evident in the emergence of the fanzine movement, the rise of ant-racist supporter campaigns and the creation of the Football Supporters Association. Since then, as the game has changed beyond recognition, creating both a feeling of disconnect between fans and their clubs and a sense of alienation amongst many supporters, this nascent politicisation has grown and blossomed. Today, fans expect to have a voice and demand this voice is heard.

But despite this psychological transformation and the growth enjoyed by the Supporters Trust movement, fan democracy could go much further with more help from those with the power to enact change.

The FA and the various league authorities have it within their remit to modify the game as they see fit. If they wanted to create a stronger relationship between supporter and club then they could. They have the power to make fan representation on the board or a degree of supporter ownership a reality, by making such a stipulation mandatory for any club competing in a particular league or competition.

Despite this, to date there has been little movement in this area from any football authority in this country. In fact, the only development of any note has been the introduction of supporter liaison officers (SLOs); employees of the club, whose responsibility it is for building bridges between the board and the fans. Initially endorsed by UEFA as part of its club licensing and Financial Fair Play regulations, the establishment of permanent SLOs across both the Premier League and the Football League has since been encouraged by the football authorities.

Although a step forward, the creation of SLOs is hardly the same as making supporter-elected directors mandatory or forcing clubs to be partially owned by the fans.

‘The problem is that the FA, the Football League and the Premier League are simply unconvinced that the supporter ownership model offers any advantages over the private ownership model that would warrant any special regime measures to assist its development,’ says Sean Hamil, former director with SD and current lecturer in management at the Birkbeck University Sports Business Centre. ‘Therefore they’re unwilling to do anything.

‘I don’t believe they are hostile to the idea of supporter ownership, there are enough positive examples, particularly in the lower divisions, to demonstrate to the football authorities that supporter ownership is a viable model, particularly for clubs either facing, or emerging from, bankruptcy. It’s just that they’re not really that interested in it.’

But the football authorities are not the only bodies with responsibility for the game. And this is where we come back to Westminster.

Since 2010, the House of Commons Culture, Media and Sport Committee (CMSC) has been looking into the issue of football governance. Experts from across the industry have given evidence to the committee, much of which contributed to the CMSC’s report into this issue that was published in 2011.

This, in conclusions that chimed with the pre-election aspirations of the two main political parties, came out in favour of greater levels of supporter involvement in the ownership of football clubs, regarding the model as ‘one of the positive developments in English football’.

It also proposed some ways that the Government could intervene to assist, such as reducing the legal and bureaucratic hurdles that Trusts face in raising finance.

As you can probably guess, none of the measures recommended have come into law and for many people involved in Supporters Trusts and fan activism, the Football Governance Inquiry represents another disappointment handed down by the politicians.

‘The inquiry has done what a lot of inquiries do, which is just kick the problem further down the line. It’s probably best to view it from a PR perspective, the Government has done it to be seen to be making the right noises,” says Dave Boyle, football writer, consultant and someone who worked for SD for many years (eventually becoming its chief executive from 2008 until 2011).

According to Dave, what the sport needed was radical action. “Part of the problem with football in this country, certainly compared to somewhere like Germany, is that it doesn’t really exist in law. There is no legal framework for the game and because of this our Sports Minister has no power. In other countries the Sports Minister can intervene in football and dictate standards and regulations to the various authorities because his power is established via a Sports Law. This is what the committee should be recommending and what the Government should be thinking about introducing.”

The creation of a Sports Law could be one of the most straightforward and simplest ways for the cause of supporter democracy to be advanced. Any such law would be able to set its own parameters, redefining the ownership structure of English football in the process. This could be as conservative as enshrining supporter representation on the board in law or providing Supporters Trusts with the first refusal to take over a club when it has gone into administration.

If it was aiming to be more radical then the law could even create a new legal form of sports club, aping the system that currently exists in much of the Bundesliga.

In Germany this type of organisation is known as an ‘Eingetragener Verein‘ (e.V) and tends to be the model adopted across many different sports. An e.V is characterised by the following rights and responsibilities; the members democratically elect representatives who manage the Verein, liability is limited to the assets of the Verein, and the club must not distribute any of these assets to its members.

The thing about e.Vs is that they are often not just football clubs. There are usually many other sports, both professional and amateur, housed under the umbrella of the club. And this is often revealed in the name. At VfB Stuttgart for example, the VfB stands for Verein für Bewegungsspiele, which in English roughly translates as a club for movement/exercise games. And at Stuttgart, these movement/exercise games include hockey, fistball and table tennis clubs that compete on an amateur basis.

Under the current regulatory framework each e.V is allowed to spin-off elements of the club, such as the football side, into separate companies. The idea behind the spin-off was for clubs to sell equity in these companies and by doing so attract outside private investment. Crucially for fans of supporter power, any spin-off comes with one major restriction. According to the 50+1 ownership rule, the e.V members must retain a minimum 51 per cent stake in the voting rights of the company.

This rule was designed to provide investment opportunities yet at the same time prevent outside investors from having overall control of the direction of the company, ensuring that the culture of the Verein remained endemic within the Bundesliga, while still enabling German clubs to compete with their European rivals.

Bayern Munich, is one such club to have taken advantage of the freedom provided by the change. Over the past decade they have sold two nine per cent stakes in their football company to Audi and Adidas. The €165m raised through this contributed to the €346m cost of constructing the club’s new stadium, the Allianz Arena. Although this has diluted the e.V’s ownership, Bayern’s members still control 82 per cent of the club’s football company (a figure that cannot fall below 70 per cent following a recent ruling passed by the e.V).

According to Jens Wagner, representative of the German football supporters’ group Unsere Kurve, both the Verein model and the 50+1 regulation are enormously popular amongst fans. “In the German game the fan is unquestionably king, which is how it should be in football. The AGM, attended by all shareholding fans, is the highest decision making body at most clubs. Only the AGM can change the club statutes and only the AGM members can elect several boards (board of directors, supervisory board etc). They wield the power. It’s no surprise then that the people who run clubs think about what the fans want. The experience the fans have is important in German football culture; they are an integral part of what makes the Bundesliga the Bundesliga.”

Although the UK tends to be a more ‘hands off’ sort of country when it comes to intervening in sport, in the area of football there are precedents for a stronger role for Government. On several occasions, specifically to tackle the issue of crowd behaviour, various pieces of legislation have been introduced over the past 35 years, such as the Football Spectators Act (1989), the Football (Offences) Act (1991) and the Football Disorder Act (2000).

Despite these precedents, Dave Boyle is unsure whether we will ever see the UK Government go as far as to introduce a legislative foundation capable of facilitating the wholesale reform of the sport. “I think the introduction of a Sports Law would require a huge culture change in Government. Even back when intervention was in fashion during the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, this country was still loathe to intervene in football. Sport is viewed differently in the UK and the laissez-faire mentality still prevails. What we probably need is a Labour Government more committed to intervention than the last lot and, at the same time a really high-profile club to go into administration, therefore precipitating a crisis. Maybe then a window of opportunity will present itself. But in the short-term, I remain sceptical.”

But even without Government help, I would not bet against supporter democracy expanding further in the future. It’s already come a long way in a short time, in the face of huge indifference from the football authorities and without anything in the way of legislative support from the Government. We might be some way from the the German model, but the rapaciously free-market mentality that dominates English football continues to be challenged at the grassroots.

Supporters have realised that they are not powerless. The days of fans meekly accepting their lot and kowtowing to the board are a thing of the past. Working together fans can achieve something remarkable. They can save clubs from extinction, bring new clubs to life and ensure that those in charge are always held to account. Even without the help of those that run the game or the country, punk football is here to stay.

Jim Keoghan is the author of Punk Football (get it here) and is on Twitter @jimmykeo

.

More articles on supporter activism

Follow SPORTINGINTELLIGENCE on Twitter