*

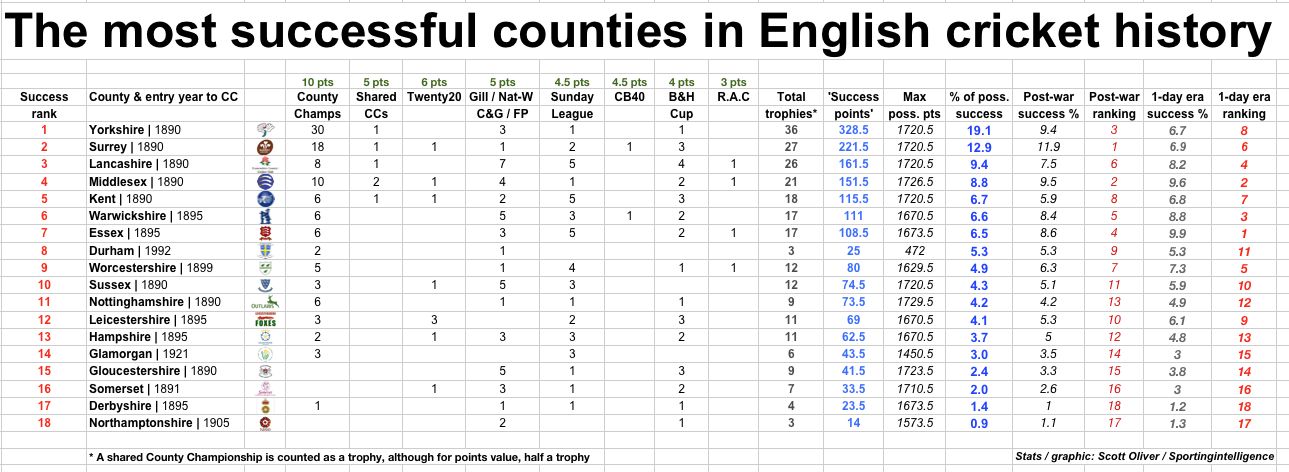

As the 2012 County Championship gets underway, Scott Oliver weighs up the most successful counties in English cricket history. And looking beyond the headline finding that Yorkshire top the all-time achievement rankings, he explains how much of their success can only be recalled through the haze of the ages, and explores how the game – and the winners – are changing in the one-day and Twenty20 era. You can also follow Scott on Twitter.

.

.

5 April 2012

WITH the 113th County Championship due to get underway today, heralding the start of the sporting summer, weather permitting, Sportingintelligence has analysed which of the 18 first-class counties have been the most successful across all formats of the game since the first formal County Championship was contested back in 1890.

There’s no debate that Yorkshire have won the major competition most – something many a real ale drinker from ‘God’s Own County’ will never tire of telling you – but the fact is that many of Yorkshire’s 30 County Championship outright triumphs (plus another shared) can now only be recalled in sepia.

Set the parameters to a more modern era and suddenly things don’t look quite so rosy (white or red).

According to our criteria – which gives different ‘weight’ to different trophies in the game – Yorkshire slip to being the third most successful county in the post-War era, behind Surrey and Middlesex, and as lowly as eighth for the period since the introduction of the limited-overs game back in 1963.

At the other end of the scale, none of Northamptonshire, Gloucestershire or Somerset have ever won the domestic game’s top prize, which is why the latter’s last session eclipse by Nottinghamshire in 2010 was so excruciating, especially as it has accompanied no less than five final defeats on limited-overs competitions. But at least the latter two have had their glory days in one-day cricket as partial compensation.

Our table of success, to be found in full below, tells you all you need to know about who’s won what. Detailed notes of what’s included can be found below the main graphic.

The ‘total trophies’ column is only one key indicator; you’ll see some counties with fewer trophies above those with more in cases where those with fewer have won more important ones, like the main one: the County Championship.

The ‘total trophies’ column is only one key indicator; you’ll see some counties with fewer trophies above those with more in cases where those with fewer have won more important ones, like the main one: the County Championship.

The three most important columns in the graphic are “% of poss. success” (which tells you the all-time percent of ‘perfection’ each county has achieved); “post-war ranking”, which measures the relative success of each county only in the years since WWII; and “1-day era ranking”, which looks at how things have unfolded since the short-form game arrived in 1963.

The methodology used is in line with that used in a previous Sportingintelligence study – to consider the most successful English football teams of all time.

As with that, a simple tally of cricket trophies would not be truly reflective of a particular county’s ‘success rating’ – not least because certain counties haven’t been in all competitions from the outset: Durham only acquired first-class status in 1992, for example, and before that, Glamorgan jumped on board in 1921; in fact, there were only eight counties in that inaugural 1890 Championship.

There’s also the fact that, as with the Carling Cup and Champions League, different trophies have different weighting, different amounts of prestige, different value.

It was therefore important to work out several figures: first, we had to assign each competition’s relative value – 10 points for the most important trophy, and so on.

Second, we calculated the total points each county had won; and then worked out what they had each competed for historically, i.e, how much hypothetical success they could have achieved.

From there, we could properly evaluate each county’s historic performance, as a percentage achieved among what might have been.

The values assigned to each competition are to an extent arbitrary; they can’t be anything else. But the logic of the points allocation is explained in detail, and in any case the overall rankings would remain the same of similar with various adjustments.

As expected, Yorkshire and Surrey dominate this list, with 36 and 27 trophies respectively and 19.1 and 12.9 per cent of the maximum possible success each – the only two counties in double figures over all time.

Assigning a rank on the basis of the percentage of possible success did not hugely alter the list from a simple ranking of total trophy wins, although Durham in eighth (up from joint 17th) are the main beneficiaries of having a relatively short life span considered..

YORKSHIRE’S historic dominance begins to wane when we evaluate more recent success, as certain counties’ figures were ‘distorted’ by success in the early years, before professionalism started to slowly even out some counties’ historical (dis)advantages.

YORKSHIRE’S historic dominance begins to wane when we evaluate more recent success, as certain counties’ figures were ‘distorted’ by success in the early years, before professionalism started to slowly even out some counties’ historical (dis)advantages.

Consider first the post-war years. Using this timeframe changed the picture considerably. The county most affected in terms of its overall historical ranking was Lancashire who famously hadn’t won an outright County Championship for 77 years until last summer’s albatross-slaying. They drop down three places from No3 in the all-time list to No6 in the post-war period, while Kent also slip, from No5 all-time to No8 post-war.

The biggest gainers when only the post-war years are considered are Essex (moving from No7 to No4, and increasing their success ratio from 6.5 per cent to 8.6 per cent), then Warwickshire, Worcestershire, Hampshire and Leicestershire.

Finally, we looked at the success of counties from 1963, the dawn of the limited-overs era and certainly a time when each county had to assemble its resources to fight on many fronts simultaneously.

During this period several counties became ‘one-day specialists’ – one thinks of Somerset in the 80s, Lancashire in the 90s, Gloucestershire either side of the millennium – not least because cup runs brought big crowds and solvency-facilitating gate receipts. The finals were big days out, too, but the greatest prestige still resided with the Championship.

As you can see from the final two columns of our graphic, the county most affected by the final shift of parameters, from post-war to post-1963, was Surrey, who won seven straight county championships between 1952 and 1958, the era of Lock and Laker, May, Loader, and the Bedser twins.

Yorkshire were also affected, albeit to a lesser extent (having four outright and one shared title cropped from the aggregate, while four from a golden run of seven titles in 10 years survived), slipping back to eighth most successful overall.

If anything, the post-1963 limited-overs era sees a greater compression of teams’ success ratings, thus a more even competition. If there were a perfect split of success between all 18 counties, a fair share would be 5.55 per cent.

In this post-63 limited-overs era, 50 not out this summer, the most successful club is less so (i.e. the top success rating is lower) in real terms than within the other two timeframes, while the bottom club is slightly higher. Meanwhile, 10 teams are above the average success marker, compared to just seven historically.

A final thing to note is that, given the dwindling Championship crowds, the corollary of which is the increased significance of bumper one-day crowds, one would expect there to be a major competitive advantage for the counties with larger, Test match-hosting grounds (which earn more).

Yet Notts come in a disappointing 12th in this period, while there are some good performances from counties without a traditional Test venue, including Leicestershire and fifth-placed Worcestershire, but headed up by Essex, who, despite not winning the most trophies in this era (that accolade is Lancashire’s), are, by our criteria, the most successful club of county cricket’s limited-overs era.

Anyway, that graphic (click to enlarge, and detailed notes on the rationale are below):

.

.

The values for the trophies were worked out as follows:

County Championship 10 points By general consensus – and despite the lustre of the big one-day finals at Lord’s – this is by far the most prestigious competition, a fact underscored by the introduction of a £500,000 prize in 2010, and the points duly reflect this.

Twenty20 Cup 6 points The more prestigious of the two current limited-overs competitions, its importance has increased since the inception of the Champions League Twenty20 in 2009 (slated for the previous year, but cancelled due to the Mumbai bomb attacks).

FP Trophy 5 points Began life in 1963 as the Gillette Cup; became the NatWest Trophy in 1981, the C&G Trophy in 2001, and the FP Trophy in 2007, before being discontinued by the ECB at the end of the 2009 season. As the oldest one-day tournament – and despite (or maybe because of, FA Cup-style) the inclusion of a fistful of Minor Counties qualifiers – this was, historically, always slightly the more prestigious of the domestic limited-overs knockout competitions.

Sunday League / Pro40 4.5 points A staple of BBC’s Sunday afternoon scheduling, this competition started in 1969 and underwent no fewer than 14 name changes (including three variations each on sponsors Axa and John Player) before being wound up in 2009, having long been confusingly scattered throughout the calendar, a sort of endorsement of Morrissey’s observation that ‘Every Day is Like Sunday’. This scores more than the Benson and Hedges not for prestige per se but because, being a league, it is notionally harder to win.

CB40 4.5 points Established in 2010 effectively as the replacement for both the FP Trophy and the Pro40. Like the latter, its early rounds are a round-robin rather than KO format (increasing the guaranteed home revenues); like the former, it has a Lord’s final.

Benson & Hedges Cup 4 points Traditionally played in 4 pools of 5 with the top two from each going through to quarter-finals, the shorter (50 overs), younger (played from 1972 to 2002) and earlier (finals played in late June or early July) B&H was the least prestigious of the ‘classic’ limited-overs competitions.

Refuge Assurance Cup 3 points The aforementioned analysis of football’s most successful English teams explicitly excluded one-off games, and we were tempted to do the same with this somewhat anomalous tournament, an event contested for four years only, between 1988 and 1991, in which the top four sides in the Refuge Assurance League (successor to the JPS League) played semi-finals and a final.

On the one hand, you could argue that it was a closed tournament, given that it was restricted to four teams; on the other, you could argue that it was open, given that all 18 counties started each season with an equal chance of participating in it. In the end, we decided to retain this competition in the calculations, albeit with a low points value, while ensuring that its semi-exclusivity was taken into consideration when working out the maximum possible points for which they competed (thus, Lancashire, who participated in all four Refuge Assurance Cups and were one of the founder members of the County Championships, have effectively competed for the most ‘points’, historically).

Champions League We excluded this from the calculations for the simple reason that, unlike its namesake in football, it lacks a crucial element of competitive integrity, inasmuch as some players can be registered with, and have played for, several of the participating teams.

Thus the overseas players used by the counties in our domestic season may well be commandeered by their IPL franchises, or perhaps play for their home teams – as happened with Keiron Pollard last year, for instance, who could have played for Somerset or Trinidad and Tobago but ended up with the Mumbai Indians. (Incidentally, including the Champions League, at a points value of 10, would not change any of the rankings, but it would mean that Somerset would displace Lancashire as the team that had competed for the most ‘success points’.)

.

Scott Oliver blogs on cricket at The Reverse Sweeper; he blogs on football at False9; and, in the latest issue of The Blizzard, tells the story of the curious short-term rivalry that took hold between Athletic Bilbao and Barcelona at the start of the 1980s. You can also follow him on Twitter.

.