26 March 2016

Goodbye to The Independent as a newspaper, published on paper for the final time on Saturday.

It’s been inevitable for some time. It won’t be the last paper to go. It’s only a question of how long it will take others to follow, not whether they will.

It’s a poignant day for those of us connected to The Indy in some way for chunks of our lives, as readers or staff. I spent 14 years working there between 1996 and 2010, most as a sports writer, a job that came by accident as I aspired to be a foreign correspondent.

One early story I worked on, nothing to do with sport, gets a mention in the final edition. An investigation done 19 years ago has reached ‘closure’ on the day the paper closes.

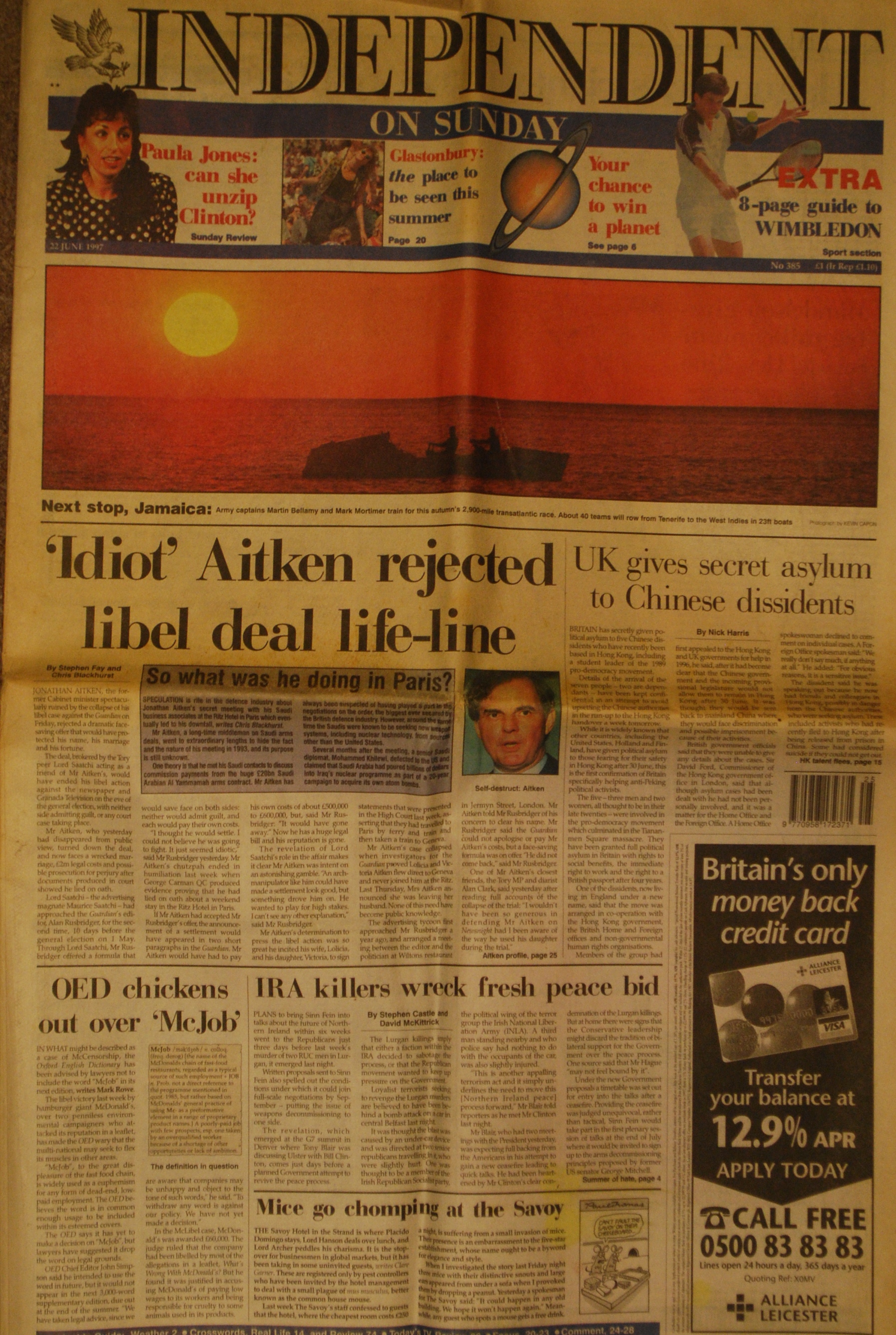

That investigation led to a front-page piece in The Independent on Sunday on 22 June 1997. I have a copy of it (left, click to enlarge), retrieved from a dusty folder.

That investigation led to a front-page piece in The Independent on Sunday on 22 June 1997. I have a copy of it (left, click to enlarge), retrieved from a dusty folder.

This was my first Sindy front page and I still recall leaving a party in Clapham at about 11.30pm on the Saturday night to go to Waterloo to get a first edition.

It won’t mean much to a non-journalist but your first byline, wherever it comes, is a thrill, so making the front page was a major buzz. In 1997 you didn’t get the next day’s front pages on Twitter. You went to the all-night stall outside a major station.

I love newspapers. Physical newspapers. I’ve got thousands in my office, collected over decades from dozens of countries. This Sindy was special because of that story: ‘UK gives secret asylum to Chinese dissidents.’

It was about a group of pro-democracy activists including former student leaders who had evaded the Chinese authorities after the Tiananmen Square massacre and had been living safely in Hong Kong, about to be handed back to China.

I’d got to know some of them when they were covertly brought to London in the run-up to the handover. I had a contact working on the tail end of Operation Yellowbird – a scheme that helped the 1989 activists to flee to foreign havens, via Hong Kong.

The British intelligence services were involved, and the CIA and several governments. The closer we got to the 1 July 1997 transfer of sovereignty, the more sensitive the issue became. The Hong Kong government, which knew about Yellowbird, didn’t want to antagonise Beijing by discussing these last ‘escapes’. Nor were the foreign states too keen on it being known they were housing these folk.

The activists were happy for their story to be known, albeit without being named at that stage. They moved to Britain with full political asylum, the immediate right to work and the right to a British passport within four years.

But there was an element of this story that ‘got away’. Or rather an element that we did not report at the time and has not been reported since. Until now.

There were two other people in that ‘last escape’ from Hong Kong to the UK who were not Tiananmen pro-democracy activists nor related to them but who were given political asylum at the same time anyway.

One of them was a teenage boy, Yin. The other was his mother, a woman called Chen Luwen who had been Chairman Mao’s last mistress. As such she had detailed knowledge not just of one of the most significant political figures in history but the last 14 years of his life and reign up to his death in 1976.

By 1997, Chen was a wealthy property trader who had also amassed a fortune as an arms dealer, with clients including Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. For various reasons she had become an enemy of the Chinese government.

She feared for her future in a China-controlled Hong Kong but found it hard to persuade any foreign government to provide her with residence. It was late in June 1997, just a few days before Chris Patten stood in the rain and passed the colony back to its motherland, that she got a call to say she could flee. ‘Pack and head for the airport,’ she was told. ‘In two hours, you’re going to Britain.’

I got to know both Chen and Yin, a little at least, that summer, and we came very close to publishing her extraordinary story in the paper. Chen wanted that to happen. We wanted it to happen. But it didn’t in the end, after a plea from a third party on safety grounds, more of which shortly.

.

AS John Lennon sang, life is what happens while you’re making other plans. Without The Independent, or specifically The Independent sports desk of 1996, my life and career might have gone in a different direction entirely.

At university, SOAS, I’d mostly thought that I’d go to work in aid and development. That had been the plan when I started my degree, and most of my class-mates went into that field, for better or worse.

But by the time I left in 1992, I wanted to be a foreign correspondent, in part because my eyes had been opened to the fascinating culture and politics of Africa, in part because I devoured The Independent and was absorbed by its foreign coverage.

It was an inspirational paper, to me at least. Aspirational. Idealistic. Sounds barmy now, and probably was then, but that’s how it felt.

But at precisely the time I was about to start a placement on the Indy foreign desk, in March 1996, 20 years ago this month, the paper hit its latest crisis and many of the foreign staff were laid off.

(I’d worked overseas for a few years, post-university, in Paris, Japan and Kenya but had come back to the UK to get a journalism diploma to try to enhance a freelance career. The diploma necessitated work placements).

The foreign desk said they were no longer able to take any workies. There was nobody to supervise them. How things change; nowadays they’d be filling the paper, if not editing it.

Instead I faxed a letter to the sports editor, Paul Newman, and he took me on a two-week placement.

Though I then went to work as a junior foreign correspondent for a couple of years for a Japanese newspaper – covering politics, economics, human rights issues, the handover of Hong Kong (hence the Mao mistress story), and Shergar’s demise among all sorts of features – I started to do regular Indy sports desk shifts on my days off from the Hokkaido Shimbun.

In 1998, Paul offered me a staff job, and, for most of the time, it was a blast.

There’s no way to avoid sounding trite and cliched when saying that the people at The Independent made it what it was. But it was true, and nowhere more so that on the sports desk, held together by manageress Nicole Wilmshurst (then and now) and assorted stalwarts.

Writers from other departments who weren’t permanently office-based would often base themselves on the sports desk when they came in. You’d find Decca Aitkenhead there, and Fiona Sturges. Later, Clive James would be in the smoking room along the corridor, dropping in to visit his mate Janet Street-Porter.

The paper was based on the 17th floor of the main tower at Canary Wharf in 1996, and although only 10 years old, already had a glittering cast of alumni from Sebastian Faulks, Bill Bryson and Helen Fielding (who started Bridget Jones in the Indy) to sports writers Patrick Barclay, Henry Winter and Paul Hayward.

Ken Jones, a legendary figure from Fleet Street’s heyday, was still there. Ken is probably the only man to have lost an arm at a sports desk Christmas party, but then the Indy sports desk has always thrown the best Christmas parties.

The two chief sports writers who spanned my time there were Richard Williams and Jim Lawton, contrasting figures in almost every imaginable way and both brilliant, and generous.

The roll call of superb Indy sports journalists who were also good colleagues is far too long to list in full; the turnover was often swift as they left for bigger papers and greater stability, often at the Guardian or Telegraph. David Conn, Andy Hunter and Greg Wood were among those who went to the former, as did Jim White, before he went to the Telegraph, who also hired Derek Pringle from the Indy, and Henry Winter, and Tim Rich and multiple others.

Among the many fine writers at the paper, I’ve made some of my closest friends.

John Roberts, who covered Liverpool in their Shankly pomp and was George Best’s ghost-writer, and who ended his career as the Indy’s tennis correspondent, is one of them. Mike Rowbottom, former long-serving athletics correspondent, guitarist and poet is another, as is the editor who hired me, Paul Newman, now tennis correspondent (who writes about the change in sports coverage over 30 years in today’s Indy).

Ian Herbert isn’t just one of Britain’s best journalists – of any genre – but also among the nicest men you’ll meet. So is Jamie Corrigan. Glenn Moore’s deep knowledge of football and consistently unhysterical approach will be sorely missed in the Indy’s post-paper days; a casualty of the ‘switch to digital’, Glenn is rare among football correspondents to have a UEFA coaching badge. The paper has already been missing the quiet diligence of another friend the Indy let go not so long ago, former sports news correspondent Robin Scott-Elliot.

One cannot do anything but wish a bright future for those remaining in the online-only operation and at the ‘i’, now sold to Johnston Press.

And you can only marvel that the Indy burned so bright for so long.

How? Certainly not via lavish resources. It seemed in perpetual chaos after the early years, always on the brink of the next financial headache.

Another former Indy colleague, Archie Bland, wrote a piece for The Guardian last month in which he posed the same question about how the paper functioned. That’s here, a recommended read.

He wrote: “The best I can come up with is that journalists at the Independent and the Independent on Sunday were, quite apart from being fiercely talented, prepared to run through brick walls for each other – and, since there were only 150 of them, hundreds fewer than their rivals, bound to accept a product that was a little rough around the edges without recrimination or complaint.”

The brick walls part resonates. I’ve worked as staff or freelance for most of the main UK national newspapers at some point and the camaraderie of the Indy at its best was unbeatable.

My perception – and this is likely flawed by bias – was also that the Independent was trusted more than many media by the people you dealt with, not least the subjects of your stories, positive or negative.

That might have been because the paper was seen as ‘small’, an underdog, itself. Or because of the title – Independent – and the ethos that underpinned it, politically and ideologically. It did feel as if it was easier to persuade people to open up or talk to the Indy, compared to other papers, as if it were somehow trusted more.

On the other hand, I think perhaps Indy journalists as a collective were – had to be – more patient and considerate in sourcing and developing stories, and contacts. With fewer staff and less money, there had to be a point of difference somewhere. The Indy’s calling card was being trustworthy and balanced and issue-based and not sensationalist or screamy or celeb-obsessed.

I’m pretty sure that some of the work we did on the sports desk in the 1990s and Noughties just wouldn’t be possible now. In the wake of the Festina doping scandal at the 1998 Tour de France, for example, we asked major British sports governing bodies if they would help us circulate an in-depth questionnaire to their stars asking them about their experiences with drugs. Most did. British Cycling didn’t. Still, we ended up with a fascinating five-day series about doping in British sport.

Nowadays, governing bodies would run a mile. Risk-averse news control is paramount, everywhere.

At the Indy in late 1999, I was still able to request, and be granted, ‘insider’ access to a top Premier League club, for a week. The club was Leeds – at their PL era peak before the fall – but I was allowed to shadow manager David O’Leary, spend time with Peter Ridsdale, quiz commercial manager Adam Pearson, go to training with Harry Kewell, Alan Smith, Jonathan Woodgate et al, and also find out about the community department, the security guards, the ticket office. Access was granted on the basis we’d do a piece about the week in the life of a whole club. We did.

At the Indy in late 1999, I was still able to request, and be granted, ‘insider’ access to a top Premier League club, for a week. The club was Leeds – at their PL era peak before the fall – but I was allowed to shadow manager David O’Leary, spend time with Peter Ridsdale, quiz commercial manager Adam Pearson, go to training with Harry Kewell, Alan Smith, Jonathan Woodgate et al, and also find out about the community department, the security guards, the ticket office. Access was granted on the basis we’d do a piece about the week in the life of a whole club. We did.

Twice, in 2000 and 2006, we worked with the PFA to carry out confidential surveys of footballers’ day-to-day lives: finding out directly from them what they earned, how they spent it, what they thought about tactics and foreign players, drugs and gambling and homophobia and umpteen other things. Both times we produced in-depth series underpinned by illustrative features that depicted the whole story, not just a bit of it.

On another occasion, after lengthy research and the establishing of trust, we were invited by the late Peter Kay of the Sporting Chance clinic to attend a private session about gambling addiction on the basis it was never for reporting without specific agreement on key details. I sat in a room that included contemporary England internationals as they recalled their various battles with debilitating compulsions, mostly alcohol or gambling. I heard a story about related spot-fixing that day that did indeed end up as a story, with Kay’s agreement, but it made it into print as part of wider issue-based package.

Evidently it’s not the case that The Independent was uniquely able to do things others couldn’t. To suggest that would be nonsense. But it felt like it was trusted to do things the right way, fairly.

Of course society and media and the coverage of all sport has changed and continues to do rapidly. The bigger the names, the higher-profile the stars, the more their images are micro-managed by PRs and spin doctors.

There are still football clubs where you can get a one-on-one interview with a big name, although probably someone will be on their shoulder listening in, and there will be an obligatory plug required for their boot supplier or a computer game.

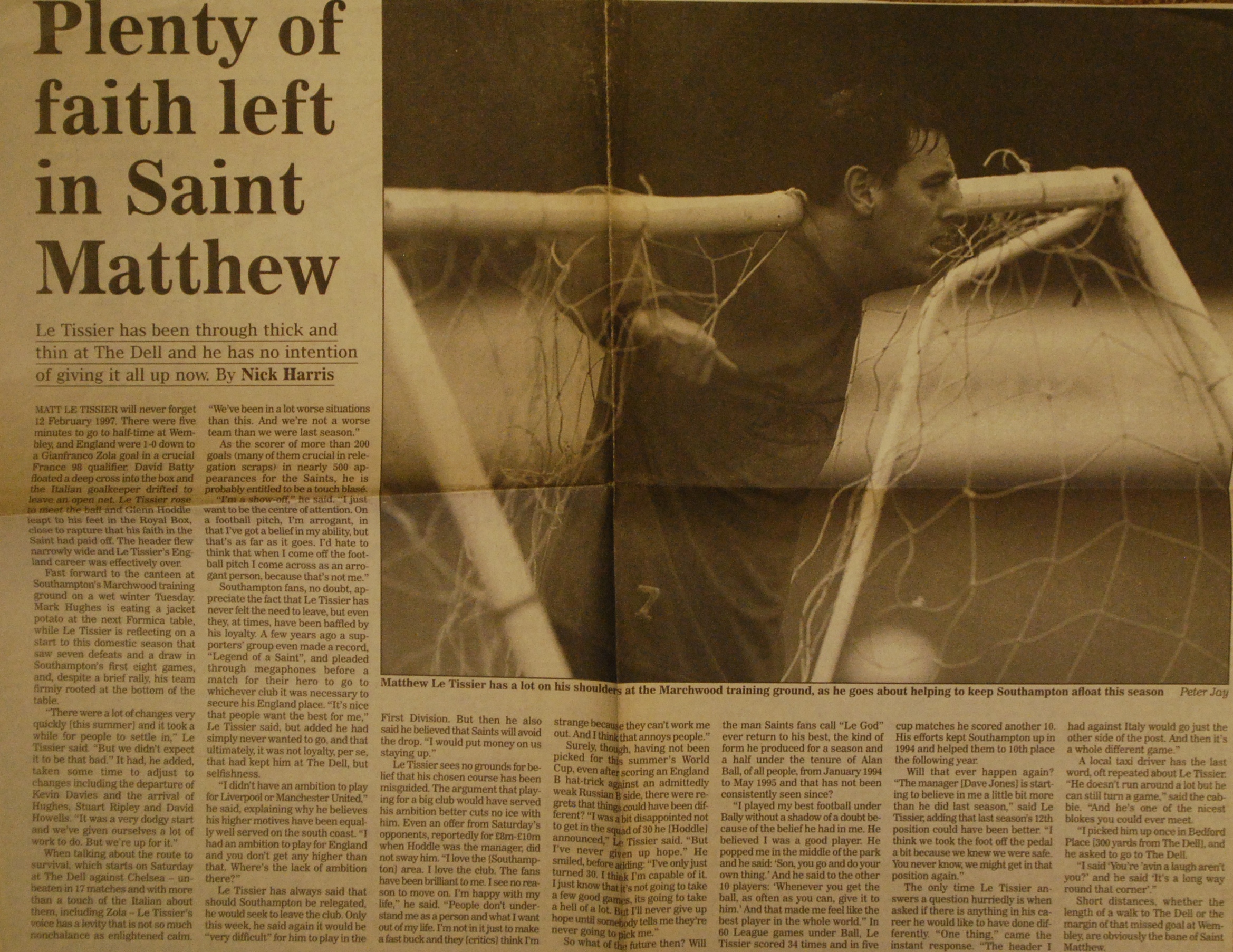

At one of my earliest interviews as an Indy staffer, in 1998 with Matt Le Tissier (my hero), it was still not that unusual to be given the run of the Southampton training ground, and sit down over lunch (jacket potato and beans) with the other players, Mark Hughes included, while we spoke. Manager Dave Jones was at the next table chatting to staff about transfer targets. Saints signed one of them, Marian Pahars, not long after that.

(The other thing I best remember about that interview was sitting in Canary Wharf, writing it up, as a super-keen work placement intern sat with me, advising me how to shape my copy. Sam Wallace went on to become the Indy’s long-term football correspondent some years later, before joining The Telegraph).

(The other thing I best remember about that interview was sitting in Canary Wharf, writing it up, as a super-keen work placement intern sat with me, advising me how to shape my copy. Sam Wallace went on to become the Indy’s long-term football correspondent some years later, before joining The Telegraph).

The Independent was always a newspaper with writers at its heart. The ‘top down’ approach where the starting point was a headline and then copy ordered to fit it, as happens in some places, was not something I ever experienced while there. Writers were trusted to know their subjects and were allowed to get on with writing. This might sound simple but it’s much less common that many readers might imagine.

Yes, those lack of resources also probably contributed to letting the writers get on with it. The paper needed their copy, so if they wanted to write on something, anything, let them write.

In turn this probably meant the Indy could be a quirkier product than some rivals. Or a bit odd, if you want to be pejorative. I prefer to think of it mostly as innovative, unafraid to try different things.

It was an honour and, mostly, a pleasure to work there. To argue the case for a story about dodgy football officials supplying black market 1998 World Cup tickets via the web and seeing it splashed on the front was a privilege. To be paid to watch Goran Ivanisevic win Wimbledon on People’s Monday, and see Federer-Nadal against each other at their peak, was ace. To go to prison for a story was strange and rewarding. To be Nick Bollettieri’s ghost writer for eight years: Holy Mackerel!

To cover Olympic Games in Athens and Beijing, and the Commonwealth Games in Manchester in 2002, which is probably still, pound-for-pound, the most fun I’ve ever had at a major sports event. An entire city bought into a festival of non-glitzy sport for two weeks and the afterglow ultimately led to London bidding for and staging the 2012 Olympic Games.

To be given time to work on esoteric features and doping or corruption stories. As long as you were working 10 hours a day churning out day-to-day content too.

There were stories that got away, scandals we could never bottom out or that got stymied by lawyers. That still happens, often.

It wasn’t a lawyer that stopped us publishing the story of Chairman Mao’s last mistress though. It was an appeal that ultimately the story might impact on people who needed safety, not scrutiny.

.

Chairman Mao’s last mistress

It was Chen Luwen herself who described her position to me as Mao’s mistress and as an ‘imperial concubine’. She was shy of her 15th birthday when first recruited in 1962 to Mao’s in-house dance troupe, and he was 68.

She stayed until 1975, the year she turned 28, when Mao was 82. She told me that between 1962 and 1971: ‘I helped him domestically about once a week.’ She confirmed that ‘helping him domestically’ was a euphemism for sexual contact. From 1971 to 1975 she lived in his complex full-time and was told to leave for own safety ahead of his death in 1976.

‘His character was very naughty. He was different from normal people. He was very charismatic and knowledgeable,’ Chen said. ‘He was an angel and evil mixed together. He was evil in politics because he cared for nothing and no-one but himself … He was an angel in regard for the high ideas of proletarian life because he was not concerned with material life, and always wore old-style clothes and ate basic foods.’

Chen was evidently wealthy, staying in an elegantly-furnished pile overlooking Regent’s Park during that summer of 1997. I had no idea what she was worth; probably millions. She said she’d lost a lot but also that she had made tens of millions from property and arms dealing.

Chairman Mao is reputed to have had multiple mistresses but the only one about whom much had been known and written about before was Zhang Yufeng, an advisor and political confidante as well as Mao’s lover.

Zhang Yufeng was around at the same time as Chen Luwen but Chen saw herself as being closest to him near the end of his life, as his ‘last mistress’.

In 1975, Chen says Mao told her to leave Beijing for own safety, perhaps because he sensed his own end was near and that his successors might want control over those who had been in around the power of Mao, her included.

Chen moved away, got married in 1976 – the year Mao died – and had her son in September 1977. Her husband was a communist official and she was dissatisfied by the marriage, which didn’t last long.

Chen said she started to become nervous about living in China after Deng Xiaoping came to power in the late 1970s. She was concerned Deng might want to have her movements curtailed or perceive her as an enemy, as someone who had been close to Mao.

With a divorce behind her, she told me that moved to Hong Kong in 1983 with her son, then six, with the aim of becoming a businesswoman. She started trading in property. She also started working on arms deals on behalf of an extremely senior Chinese official, Yang Dezhi, who she said she got to know via her association with Mao.

Yang had become the chief of staff of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in 1980 and was heavily involved in arms procurement. Chen says Yang was hugely respected and a very good man and a man of principle. (Later on, Yang clashed with Deng over Tiananmen Square. Deng was a hardliner who ultimately ordered in the tanks. Yang was against the strategy of using the PLA against the people, and against martial law being imposed in the city).

Chen said her role in the arms deals was as a ‘middle woman’ who ‘helped to facilitate’ the buying and selling of weapons. She hosted related meetings in Hong Kong that the Chinese couldn’t. It was easier for those involved from outside China to do their business there, she said. She mentioned two specific deals she was involved in, both in or around 1985. One was buying military helicopters for China, from France. The other was selling Chinese land-to-air missile to Saddam Hussein for Iraqi use in the Iran-Iraq war. She told me that deal was worth $300m.

The arms dealing appears to have got her into trouble in China, because when she went back to China in 1986 for a family visit, she told me was arrested in the car park of her hotel, taken away from her son, and put under effective house arrest for 18 months.

She told me she thinks this happened because Deng Xiaoping was annoyed at Yang Dezhi (the senior official who put the arms deals her way). Deng’s son-in-law, a man called He Ping, had via nepotism been allowed to take control of much of China’s arms trade and Yang had criticised this.

Hence Deng and Yang were at loggerheads, and Chen believes this is why she got the 18-month ‘shot across the bows’ house arrest. She says the reason she was given for being put under house arrest was the state alleged she had been betraying Party secrets outside China by talking about her life with Mao.

When General Yang ‘retired’, or more likely was engineered aside, in 1987, Chen was allowed to leave house arrest, although not leave China. (Again, she says, the authorities were concerned she would tell people outside China about Party secrets).

She stayed in China until 1989, reunited with her son, but was unsettled by the Tiananmen massacre and the state of China in general, and decided to flee to Hong Kong. She says she was smuggled out of the country by Triads, to whom she paid a six-figure sum in US dollars. ‘My right of abode in Hong Kong at the time was personally signed by the Governor [of Hong Kong],’ she told me.

Back in 1997, I asked the relevant departments in Whitehall about Chen’s story and received what was in effect a ‘we wouldn’t comment on this kind of confidential issue’ response. I did not manage either to get a response from the Hong Kong governor in 1989, Sir David Wilson.

Chen and her son lived in Hong Kong from 1989 to June 1997, and got out with days to spare before the handover.

Many years later, in 2011, the memoirs of a late democratic Hong Kong politician, Szeto Wah, were published posthumously and made reference to an unnamed ‘mistress of Mao Zedong’ who had helped out of Hong Kong by Operation Yellowbird. The description of the woman matched Chen Luwen’s story, from details about her to her past as a dancer and arms dealer, to having been held under house arrest to paying Triads to help her flee to Hong Kong.

In 1997 when she fled to London, she bought few possessions but did bring some photos, one of which she allowed us to photocopy (left), of a group of young women, herself and Zhang Yufeng included, in Mao’s harem of 1975. Chen is third from the right on the front row and Zhang is on her left side.

In 1997 when she fled to London, she bought few possessions but did bring some photos, one of which she allowed us to photocopy (left), of a group of young women, herself and Zhang Yufeng included, in Mao’s harem of 1975. Chen is third from the right on the front row and Zhang is on her left side.

It would have been a politically explosive story to run just days before the handover of Hong Kong. Ultimately one of those involved in Yellowbird petitioned that Chen’s asylum in England might have unforeseen consequences for the pro-democracy activists Britain was trying to help.

There was some intense debate in the office about what to do before we decided to hold the story of Chen. It was always my intention to revisit it, probably a few months later, perhaps on the anniversary of the handover.

I stayed in touch regularly with Chen and Yin until later in 1997 until one day nobody answered the home phone in Regent’s Park and the mobile numbers stopped working. Chen had talked about a desire to live in America and my assumption has always been they stayed in the UK just a few months and moved on, probably there.

But I don’t know.

One day they were there; fascinating, thought-provoking, intriguing, exciting. Something a bit different. And then they were gone.

Like The Independent.

.

Follow SPORTINGINTELLIGENCE on Twitter